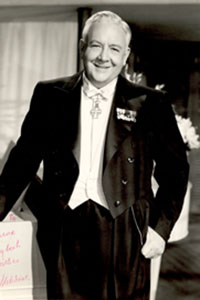

The History of Lauritz Melchior

Born: 20th of March 1890, in Copenhagen

Died: 18th of March 1973

Danish Tenor

The greatest tenor of the century in his own field, brings us to the Great Dane Lauritz Melchior, born on the 20th of March 1890, in Copenhagen.

This great Wagner specialist dominated his field as no other since the advent of recording.

And as the years passed by, he remains approached and yet in his own time, he was almost taken for granted.

Having sung as a boy soprano, he trained at the Royal Opera school in Copenhagen and made his debut at the Royal Opera House there, on the 2nd of April 1913 as Silvio in Pagliacci, going on to sing various other baritone roles.

Subsequent studies with a Danish Tenor Vilhelm Herald, revealed the true nature of Melchior’s voice, and he made a second debut in the same theater on the 8th of October 1918, in a title role of Tannhauser.

With the help of the English novelist, Hugh Walpole, (who heard him sing at a London concert in 1919), Melchior was able to study the Wagner repertoire intensively with Anna von Milden Berg and other eminent teachers. And made what might be termed a third or international debut at Covent Garden on the 14th of May 1924, as Sigmund.

Later that year he sang Sigmund and Parsifal at Beirut and returned there regularly until 1931.

From 1926 to 1939, he appeared every year at Covent Garden, where he quickly became a main stay of the Wagner repertory, especially as Sigmund, Siegfried, and Tristan. Othello, sung either in German or in a very Teutonic sounding Italian, was his only other non-Wagnerian London role.

Melchior’s metropolitan debut on the 20th of February 1926, as Tannhauser, was not outstandingly successful.

His great New York period began only with his return after absence and further study, to sing Siegfried and Tristan in 1929. Hence forward, his activities centered on the metropolitan, he had remained a pillar of the Wagnerian wing for more than 20 years. Until disagreements with the Bing regime caused him to take his leave as Lohengrin on the 2nd of February 1950.

During those years, he made frequent guest appearances in Europe, and at The Cologne in Buenos Aires. Laterally, he scored some success in Broadway shows and films, but continued also to make concert and radio appearances, in his old repertory, even singing Sigmund, with the Danish radio orchestra in March 1960 to celebrate his 70th birthday.

Here he is in full throttle. Siegfried’s ‘Forging Song’ and Lohengrin’s ‘From Distant Lands I Come’.

Nothung ( Forging Song ) / Seigfried / 1930 – Lauritz Melchior

In Fernem Land / Lohengrin / 1939 – Lauritz Melchior

John Stein writes.

‘Even today we have probably not realized how phenomenal Melchior was.

One is tempted to see an odd kind of perversity in the incomplete recognition, for without him, we would have a limited notion of how well Wagner’s tenor roles can sound. But where Lidar and Shuar are venerated, Melchior is merely acknowledged.

Many of today’s senior critics, no doubt remember him as a bulky unromantic figure on the stage, remote from any ideal conception of Tristan or Siegfried.Certainly, later in his career, the voice lost some of its glow, and his interpretations of some of the sensitivity and it is always said that he could be maddeningly and persistently inaccurate.

Irvin Culloden mentions a famous remark of one conductor to another, when the general unreliability of tenors.

Adding that at least you knew where you were with Melchior, because he always made the same mistakes.I believe that a private recording of Melchior singing Othello is in existence, but of his recordings made in German in 1927, are anything to go by, it should have been the performance of a lifetime.

For the monologue and death scene have rarely been more fully realized than in these.

Everything is most deeply felt, yet the emotion is contained, so that unlike Zanelli’s great performance, he feels no need to leave the reciting note to express the tragic force of the words. Then to suggest a few more comparisons, his voice is in so much better form than was Martinelli’s, when he came to make his Victor recording, (also superb in its way), in 1939.

He can rise easily in that strangely difficult final phrase of the revutation, and his sweetened tone to the high ‘G’ rounding off the passage softly and rather wistfully, in the way that John Vickers does.But in this comparison too, I found Melchior generally preferable, for there is a greater impression of spontaneity, and there is a more exciting shine on the voice. These are all exceptional performances but alone among them Melchior seems to have it less than its critical due.

Dio Mi Potavi Scagliar / Otello / 1930 – Lauritz Melchior

Desmond Shaw Taylor writes.

In his later years, Melchior sang little but Wagner, and concentrated on the heaviest roles, in each of which he appeared over 100 times, as Tristan over 200 times. These figures suggest something of the stamina and endurance that made-up this huge Dane, huge in every dimension, as in voice.

The only Wagner tenor of recent times, who could still sound fresh in the last acts of Tristan and Gotterdammerung.A certain baritonal warmth remained a welcome feature of his singing, but there was no corresponding constriction in his top notes, and Siegfried’s lusty High “C” in the scene with Rhine maidens, always rang thrillingly through the house.

These varchars, coupled with a vivid and expressive annunciation of the text, induced his admirers to overlook his dramatic limitations, and even some musical defects. Vagueness in the matter of rhythm and note values, which caused him to avoid the more lyrical and musically complex role of Walter in Master Singer. The heroic scale of his singing, whether in recollection or as experienced again, through the gramophone, has made it increasingly clear, that he was the outstanding Haldon tenor of the century.From 1913, in his baritone days, Melchior recorded extensively for numerous companies. His best pre-war years are fully documented, by his recording as Sigmund with Lotte Lehmann and Bruno Walter and by a composite but almost complete account of the young Siegfried music, supplemented by substantial extracts, from Gotterdammerung, Tristan, Lohengrin and Parsifal, either with Freda Lidar or with Kirsten Flagstad, the two great Wagnerian Sopranos of the age.

He died in Santa Monica, California on the 18th of March 1973, just two days short of his 83rd birthday.

And so, to finish, another rare opportunity to hear him in a non-Wagnerian role. That of the explorer Vasco da Gama, discovering his paradise in Meyerbeer’s L’Africaine.

And then in his true element as Tristan, with one of his greatest partners Frieda Lidar, but for a change, I’ll let John Stein introduce that one for himself.

O Paradiso / L’Africaine / 1929 – Lauritz Melchior

John Stein:

Beecham’s work with the orchestra was seen by Kadri’s, as the crowning glory of his career up to that point. In the garden music, as he called it, of Tristan Act 2, the textures were wonderfully murmurous, somehow hidden in secret, full of dark and lovely whisperings and suspense. As for Lidar and Melchior, as the protagonists, they had never been finer.

Lidar never so absolutely sure of herself. Melchior so skillfully blending his voice with hers.

That they could also manage some skillful blending, even in the absence of Sir Thomas, is clear from their recording, where the conductor is Albert Coates.

Garden Music with Lieder / Tristan / 1929 – Lauritz Melchior

The History as it was Recorded

Sydney Rhys Barker