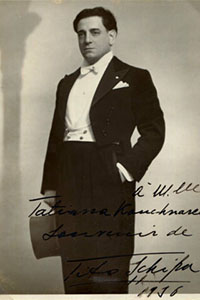

The History of Tito Schipa

Born: 27 December 1888

Died: 16 December 1965

Italian Tenor.

Occasionally, a tenor appears with a voice so light, that its scope is almost totally confined to the purely lyric repertoire.

Two operas such as Traviata, the Barber of Seville, Elisir Damore as Italian examples, Mano, Pearl fishers and Vagne in the French repertoire, and Sadco, Maynight and Eugene Onegin in Russian. Naturally with a limited repertoire, very few attain great international fame.

The much richer and broader repertoire of the lyricos pintos and Augusto’s, including as it does, the popular verismo operas, became more popular today. Not to mention the publics preference for the bigger and richer sound of these type of voices. However, every now and again an exceptional lyric tenor appears, by the very nature of his outstanding gifts, joins the elite amongst the tenor hierarchy. Bonci, Clement, Lewinski, and Smirnoff have already been heard.

And another Prince of the genre, was undoubtedly, Tito Schipa, born on the 2nd of January 1889, in southern Italy. Looking through his career, reminds me somewhat, of Giuseppe Anselmi, in that Schipa was a fine all-round musician, composing an operetta, a mass for chorus and a mass for four voices, in addition to many songs and piano pieces.

Unlike Anselmi, he recorded some of his own songs. His main studies were conducted in Milan, and they were extensive, lasting six years in all. It was in a town of Acceli, in 1910 that he made his debut in La Traviata, and he toured the province’s, building up a reputation.

It was in 1913, that he first appeared at the Dal Verme, Milan, where he was heard in Traviata and Tosca. Then straight onto the Cologne in Buenos Aires, for performances of Minion with Barrientos, Traviata with Barrientos and Scrattiari, and finally in Latme, again with the brilliant Spanish coloratura Maria Marrientos. He certainly was lucky with his songbirds, for his next appearance in Milan, with Galli-Curci, in Silambula, Rigoletto and Traviata, the start of a famous partnership.

In 1914 he made his debut in two famous houses, the Constanza in Rome, and the San Carlo in Naples. Before returning to the Cologne for another season, the outstanding performance of his, being in La Salambuila with Barrientos, and Journee. Another outstanding event was the war charities special season, in the Dal Verme in 1915, which Toscanini organised. Schipa sang in Traviata, il Scorpio and Scrattiari.

His la Scala debut was in Boliden’s, Prince Eaga of all things, but soon after, he took over the tenor lead in Mano from Bonci. Back to the Cologne again from 1916, more collembolas and barbers with Barrientos, and in Falstaff with Ruffo. Back to Europe for his first Spanish appearance, before arriving in Monte Carlo for the world premiere of Puccini’s la Raugenet, which took place on the 27th of March 1917.

No records from his creator role again I’m afraid, I’m sorry to harp on about this, but how anyone could put down 270 plus sides on record, including in this case some very poor songs indeed and yet not include something from his one operatic moment of historic importance, simply defies belief.

Anyway, here he is in Handel’s famous Largo, which is in fact, the Ombra Mai Fu from his Opera Xerxes.

Ombra Mai Fu (Largo) / Xerxes / 1926 Ombra Mai Fu (Largo) / Xerxes / 1926 – Tito Schipa

The Great War interfered with his usual journeys to and fro from South America. German submarine activity, preventing safe passage.

One famous victim being the Spanish composer, Granados, drowned at sea when his ship was torpedoed.

With the war at an end, he sang first at the San Carlo in Naples, before crossing to the United States for his eagerly awaited arrival at Chicago. His debut was on the 4th of December 1919 in Rigoletto, opposite Galli-Curci. Over the next 20 years, Schipa was to become one of the city’s greatest celebrities, singing in 200 operatic performances there.

During this time, he sang in 34 Traviata’s, 31 Barbers, 30 Martha’s, 16 Lakme’s, 11 Mano’s 10 Lucia’s, 9 Minions, 8 Don Pascale’s, 8 San Ampulla’s, 7 Rigoletto’s in addition to Amico Fritz, Romeo and Juliet, Lucia de Lammermoor, Falstaff, Tosca and Fradiavalo. And his songbirds included the Germans Lidar and Evogen, Italians Storcio, Muzzio, Dalmonte and Raiza, the Spaniards Bore, Porretto, and Hidalgo, Russian Bourschia, the Chezch Innovotna, and the Americans Edith Mason, Grace Moore and Mabel Garrison and of course, Galli-Curci.

Here they are, a match made in heaven, if ever was one.

Son Geloso w Galli-Curci / Sonnambula / 1923 – Tito Schipa

During his period in America, Schipa became a concert recitalist of great repute. Being a musician himself, as well as a singer, he was able to encompass a large concert repertoire, and he was a man of great charm and personality.

He appeared frequently at Carnegie Hall in New York, and Boston’s Symphony Hall. In addition to his very popular concerts in Chicago. For the first time for 11 years, Schipa returned to the Cologne in Buenos Aires, in the summer of 1927.

He was heard in four performances of Traviata with Muzzio, and five of the Barber with Dalmonte.

In December 1929, he returned to his native Italy after a long absence. He made his re-entre at La Scala in Evrasia Damore.

Don Giovanni was his other Scala role that season.

All Italy was clamouring to hear him, and it was now a question of trying to fit in as much as possible.

He appeared in Rome, Naples, and Florence, before deciding a tour was the only solution. In the spring of 1930, he began the first of 35 concerts, which would take him all over southern Italy and Sicily, before departing for the Cologne for some famous performances of Donizetti’s Don Pascale.

Unknown – Tito Schipa

Schipa spent most of 1932 in Italy, singing opera at La Scala and in Rome, and no doubt preparing for his debut at the Metropolitan, which was to be in November of that year.

His debut there, was in Evrasia Damore and it was highly successful. His other roles that season, were Don Giovanni and la Traviata.

He was at the Metropolitan again from 1933, this time singing in Minon with Bore and Ponze, Traviata with Muzzio, Don Giovanni with Pinza, and Ponselle, and Mano with Bore and De Luca, and back yet again, in 1934/35 for Don Giovanni, Mano, Traviata, Don Pascale, Minion, Sonambula and Lucia, a very busy season indeed for our singer.

We have not yet had a critical report of any of his performances. So, let’s hear what Olen Downs, the operatic critic of the New York Times had to say about his metropolitan debut.

He had a well-deserved success. The voice may be a little drier than a decade ago, but the skill and song, and the art of the musician were obvious in everything the singer accomplished. Mr Schipa had ample bravura when that is required. But what is more to the point in this adorable opera bouffe of Donizetti, is his capacity to sustain and mold beautifully, a long melodic phrase.

He also makes much of the text, in all these requisites of artistic singing, Mr Schipa won the respect and enthusiasm of his audience. His authority as an interpreter was tinged, with his capacity for fun. And in appropriate places, he made the audience laugh without becoming a mere buffoon. Thus, he kept within the frame of Donizetti’s comedy, which like all other operatic comedies of this period and style, is often spoiled by cheap vocal tricks and cheap silly canning.

At no time did Mr Schipa depart from artistic standards, and on no occasion did he fail to charm, as well as divert his listeners.

The climax of his performance came naturally, Una Fortiva Lagrima, delivered with much refinement and feeling and here the audience not only applauded but shouted its approval.

Una Fortiva Lagrima / L’Elisir / 1925 – Tito Schipa – Tito Schipa

When the Met’s season ended, it was back to la Scala for performances there. Medo with Causio, Don Pasquale and the Barber of Dalmonte, another famous partnership. Fancy finding someone like Dalmonte after Galli-Curci? How lucky can you get?

Next at la Scala came Traviata and Verta, and at the Cologne, la somnambule with the French sensation Vo Lipon. And of course, he was still singing regularly at Chicago.

But he was careful, as we can see he sang only the lyric role, and never stretched his voice, which was obviously the reason for its longevity. He was now singing regularly at la Scala, and we find performances of the secret marriage, Le Lisiana Marsella, in addition to his now popular roles there.

He returned to the metropolitan in 1941, for his last season there, singing Don Giovanni with Millanoff, Novotna, Saioff, Pinza and Bacaloni. And the Barber of Seville with John Charles Thomas, Pinza and Bacaloni. This last Boston with the metropolitan company.

Schipa spent the war in Italy appearing as often as war conditions would allow.

As soon as hostilities ended, he was back in harness immediately, straight back to the Cologne for 1946, singing his familiar and favorite roles.

His final Scala appearances were in 1949 in the Barber, the Secret Marriage and Verta, and we note that he is now singing with the new emerging stars of the 50s, Tito Gobi, Forest Kristoff, Elda Goudan, Al Danone, Fedora Barbarvieri, Sseko Briskentini, Guile Yeuneri.

Still very active as a concert artist, Schipa made a farewell appearance in Britain in 1951 at the age of 62.

He had never been engaged for Covent Garden strangely. I was lucky enough to attend his concert in Glasgow on the 16th of November 1951.

I thought that he would sing nothing but songs, not daring to risk the operatic items.

Not a bit of it. Out came Mapari, Afouai, Gousimage, and Aino meridistat, brave efforts indeed.

I always have a habit of shutting my eyes at some point during the recital, just to hear the voice without any other distraction.

Schipas voice sounded a little drier than in his best days and the top notes were definitely spreading, but the timbre and the velvet were still there intact, what a marvelous tribute to his teachers and their methods and to the man himself, never extending his unique voice beyond its capabilities.

One final impression I carry with me; when he entered, he received an ovation.

He had never sung in Glasgow, and I’m sure it was quite unexpected.

As he bowed, his eyebrows shot up in surprise.

No one was clapping harder than I.

Ah Non Mi Ridestar / Werther / 1925 – Tito Schipa

The History as it was Recorded

Sydney Rhys Barker